Site pages

Current course

Participants

General

Module 1: Introduction and Concept of Soil Erosion

Module 2: Water Erosion and Control

Module 3: Wind Erosion, Estimation and Control

Module 4: Soil Loss- Sediment Yield Estimation

Module 5: Sedimentation

Module 6: Topographic Survey and Contour Maps

Module 7: Land Use Capability Classification

Module 8: Grassed Waterways

Module 9: Water Harvesting

Module 10: Water Quality and Pollution

Module 11: Watershed Modeling

Keywords

Lesson 26 Land Evaluation and Improvement

Land evaluation is concerned with present land performance. Frequently however, it involves change and its effects, with change in the use of land and in some cases change in the land itself.

26.1 Definition of Land Evaluation and Difference between Land Evaluation and Land Capability Classification (LCC).

Land evaluation is formally defined as 'the assessment of land performance when used for a specified purpose, involving the execution and interpretation of surveys and studies of land forms, soils, vegetation, climate and other aspects of land in order to identify and make a comparison of promising kinds of land use in terms applicable to the objectives of the evaluation'. Land evaluation can be a key tool for land use planning, either by individual land users (e.g., farmers), by groups of land users (e.g., cooperatives or villages), or by society as a whole (e.g., as represented by the governments). There is a diverse set of analytical techniques which may be used to describe land uses, to predict the response of land to these both in physical and economic terms, and to optimize land use in the face of multiple objectives and constraints. Land evaluation should also be distinguished from land capability based classification as used, where land capability is based primarily on an assessment of soil conditions to support common cultivated crops and pasture plants. The land-evaluation approach, on the other hand, additionally takes into account specific crops and aspects related to land-management and socio-economic setting.

Land evaluation provides practical answers to such questions as

What other uses of land are physically possible and economically and socially relevant?

What inputs are necessary to bring about a desired level of production?

What are the current land uses and what are the consequences if current management practices stay the same?

26.2 Land Evaluation Framework

The range of possible uses of land and purposes of evaluation is so wide that no one system could hope to take into account all of them. Besides such obvious contrasts as those of climate; differences in the availability and cost of labour, availability of capital, population density and levels of living will all cause differences detail and emphasis in the evaluation of land.

It was recognition of this situation, coupled with the need for some degree of standardization or compatibility which led to the concept of the Framework for Land Evaluation. The framework does not by itself constitute an evaluation system. The framework sets out a number of principles involved in land evaluation, some basic concepts, the structure of a suitability classification and the procedures necessary to carry out a land suitability evaluation at local, national or regional scales.

Principles of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Framework for Land Evaluation:

Land suitability should be assessed and classified with respect to specified kinds of land use and services.

Land evaluation requires a comparison of the benefits obtained and the inputs needed on different types of lands to assess the productive potential, environmental services and sustainable livelihood.

Land evaluation requires a multi-disciplinary and cross-sectoral approach.

Land evaluation should take into account the biophysical, economic, social and political context as well as the environmental concerns.

Suitability refers to use or services on a sustained basis; sustainability should incorporate productivity, social equity and environmental concerns.

Land evaluation involves a comparison of more than one kind of use or service.

Land evaluation needs to consider all stakeholders.

The scale and the level of decision-making should be clearly defined prior to the land evaluation process.

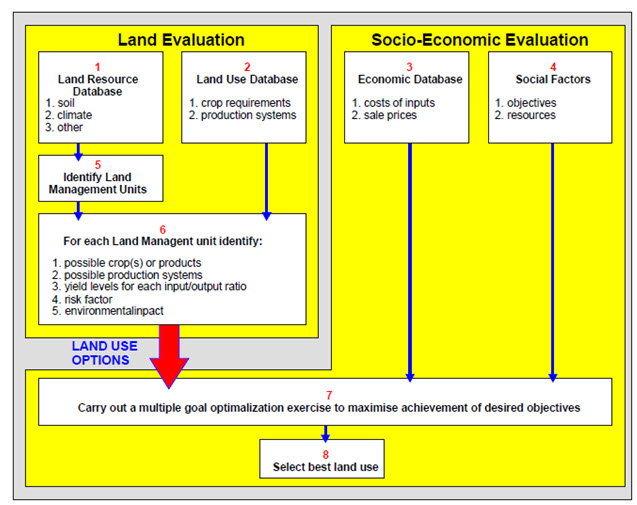

The principles and procedures given in the Framework can be applied in all parts of the world. They are relevant both to less developed and developed countries. At one extreme, they can be applied to areas where development planning is being applied to the more or less unaltered natural environment; on the other, to densely populated lands where the main concern of planning is to reconcile the competing demands for land already under various forms of use. The Framework can be used to construct systems applicable at all levels of intensity ranging from, at one extreme, national, continental or world-scale assessment, and at the other to detailed local studies. The Framework covers all kinds of rural land use: agriculture in its broadest sense, including livestock production, together with forestry, recreation or tourism, and nature conservation. Engineering aspects involved in rural land use, such as foundation suitability for roads or small structures are also included. The Framework is not intended for the distinct set of planning procedures involved in urban land use planning, although some of its principles are applicable in these contexts. Nor does the Framework take into account the resources of the seas. Water on and beneath the surface of the land is, however, of relevance in land evaluation. The FAO advocates decision-support systems, in which physical land evaluation and socio-economic evaluation run parallel for planning of sustainable use of land resources (see Fig. 26.1.)

Fig. 26.1. Decision Support System for Land Use Planning.

(Source: FAO, 1995)

This Framework is written mainly for those actively involved in rural land evaluation. Since most land suitability evaluations are at present carried out for the purposes of planning by national and local governments, this situation is assumed in references to decision-making, but the evaluation can also be applied to land use planning by firms, farmers or other individuals. The principles and procedures which are set out can be applied either to land evaluation for individual land development projects or to the construction of local or national evaluation systems.

26.3 Land Degradation

The risk of land degradation stands at the root of land evaluation. Land degradation is damage to land that makes it economically less useful and biologically less diverse. Degradation of the natural environment is a worldwide problem, and some examples are quite ancient. This term is used specifically to refer to damages caused by human activities rather than natural ones, and human activities can indirectly contribute to environmental changes that may accelerate the speed of land degradation. In land degradation, land that was once rich in nutrients and able to support diverse organisms becomes compromised. Some types of degradations include development of salinity and acidification of soils, topsoil loss, soil compaction and pollution of land due to which it becomes unusable. The more degraded the soil becomes, the less it can support. This can cause degradation to speed up, as plants and animals that would normally help restore the soil are unable to survive.

Natural causes often determine the inherent capacity of the ecosystem to provide goods and services. They include the factors related to climatic condition, availability of water in adequate quantities, the capacity to generate biomass, provide ground cover and biodiversity. Some natural causes such as slope and soil vulnerability to water and wind erosion also influence the degradation processes.

Human-induced causes of land degradation processes are largely determined by land use and land-use change, economic factors related to the possibility of investing in the land and access to markets; and social factors that assure the availability of infrastructure, and farmers’ accessibility to land that allows them to produce at maximum capacity. Agricultural practices are common culprit in land degradation. Overworking the soil can damage it, sometimes permanently. Degradation can also be the result of overutilization of timber resources that de-stabilizes the ecosystem. As the trees are cut down, the organisms they support are no longer able to survive. The land and soil face many difficulties like deforestation, erosion, flooding, water logging, urbanization and salination. Soil erosion occurs everywhere in the world. It is more common in the Australia, India, Spain, U.S.A and Africa where air and water erosions affect around 40 thousand hectares of land annually. Apart from the direct and obvious causes of human induced land degradation, there are often other more deeply rooted drivers that have serious repercussion. They include population pressure, poverty, lack of markets and infrastructure, poor governance and weak institutional frameworks and inadequate education.

Land degradation is more than an environmental problem alone and should be considered holistically taking into account different ecosystem goods and services, biophysical as well as socio-economic. Results should be referred to a given time period and solutions require full consultation with stakeholders and imply trade-offs between environmental and socioeconomic ecosystem services. Degraded land, based on the capacity of the globe’s ecosystem to deliver goods and services are highly variable. Degraded land mostly occurs in dry and steep lands which deserve special attention. Degradation takes many forms and it affects soils, availability of biomass, water, biodiversity, economics and social services derived from the ecosystem. This decline (degradation) appears to be proportional to the present capacity of the system. In other words ecosystems with lower capacities decline at a less rate than the ecosystems with greater capacities. The impact of this degradation is most felt in areas with a high incidence of poverty. This implies that even when starting from a low resource base, the lower rate of degradation in these areas has a much greater impact, compared to the ecosystems with a higher capacity, with a higher rate of degradation, but with fewer poor people.

The process of restoring land that has become degraded is known as remediation. In remediation, people identify the causes of the land degradation and explore the methods for reversing it. Usually remediation takes time, as scientists want to encourage the land and ecosystem to rebuild and become stable again rather than enacting a quick fix. In some cases, land is too badly degraded for remediation to be effective, forcing human populations that relied on the land to relocate in order to access new resources. This in turn can contribute to population pressures in other fragile environments, ultimately repeating the land degradation all over again.

26.4 Land Improvement

Land improvements are activities which cause beneficial changes in the qualities of the land itself. Land improvements should be distinguished from improvements in land use. Land improvements are classed as major or minor. A major land improvement is a substantial and reasonably permanent improvement in the qualities of the land affecting a given use. A large non-recurrent input is required, usually taking the form of capital expenditure on structure and equipment. Once accomplished, maintenance of the improvement remains as a continuing cost, but the land itself is more suitable for the use than before. Examples are large irrigation schemes, drainage of swamps and reclamation of salinized land.

A minor land improvement is one which has either relatively small effects or is non-permanent or both, or which lies within the capacity of individual farmers or other land users. Stone clearance, eradication of persistent weeds and field drainage by ditches are some of the examples. The separation of major from minor land improvements is intended only as an aid to making a suitability classification. The distinction is a relative one, that is, it is not clear-cut and is only valid within a local context. In cases of doubt, the main criterion is whether the improvement is within the technical and financial capacity of individual farmers or other landowners. In many areas improvements such as subsoiling, dynamiting or terracing cannot be undertaken by individual farmers, and are therefore regarded as major land improvements. In countries with large farms and high capital resources coupled with good credit facilities, however, these changes may be within the reach of individuals and are therefore considered as minor improvements. Field drainage is another improvement that may or may not be regarded as major, depending on farm size, permanency of tenure, capital availability and level of technology.

Keywords: FAO, Land Evaluation, Land Improvement

References

F. Nachtergaele, R. Biancalani and M. Petri. (2009). Land degradation. SOLAW Background Thematic Report 3.Rome, FAO

Suggested Readings

F. Nachtergaele, R. Biancalani and M. Petri.(2009). Land degradation. SOLAW Background Thematic Report 3.Rome, FAO

Dhillon, S. S. (2004). Agricultural Geography. Tata McGraw-Hill Education