Site pages

Current course

Participants

General

Module 1. Role of mechanization and its relationsh...

Module 2. Performance and power analysis

Module 3. Cost analysis of machinery- fixed cost a...

Module 4. Selection of optimum machinery and repla...

Module 5. Break-even point and its analysis, relia...

Module 6. Mechanization planning

Module 7. Case studies and agricultural mechanizat...

Topic 8

Topic 9

Topic 10

Lesson 25 and 26

Agricultural mechanisation plays a complementary role in increasing production, productivity and profitability in agriculture by achieving timeliness in farm operations, bringing precision in metering and placement of inputs thereby reducing input losses and reducing unit cost of production. Agriculture still continues to be the principal means of livelihood for over 58.4% of population in India. Cognizance has to be taken of the fact that the next generation of farmers would not be interested in farming unless it is profitable and mechanised in comparison to alternate opportunities in the society.

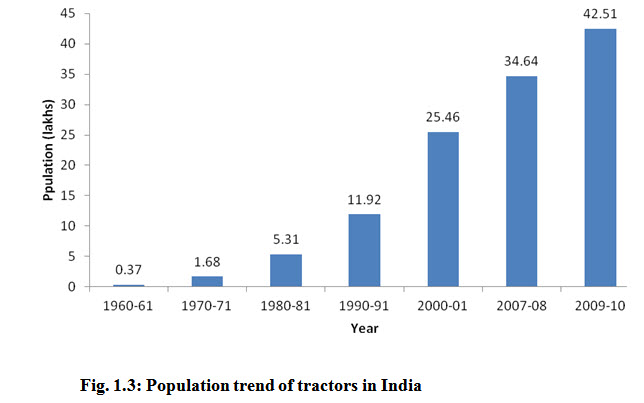

Tartarisation has been recognised as the main driver of farm mechanisation for mitigating drudgery and increasing the level of farming, so as to improve the life and work environment of farmers. At present in India, tractors are being used for tillage of 23% of total area and sowing in 21.3% of total area. In addition, irrigation pumps and tractors, threshers have been adopted on large scale across the country. Combine harvester, reapers, potato, groundnut and sugarcane mechanisation machinery have also shown commercial success. Now combine harvesters are commonly used in different parts of the country on custom hiring basis for wheat, soybean and paddy harvesting.

Although utility of manually and bullock operated equipment has been established their acceptance has been rather limited. Due to limited annual use and economic advantage, some improved implements could not replace the local alternatives. The reason for mechanisation is mainly economic and timeliness of operation as indicated in desired outputs such as an increase in labour productivity, increase in land productivity and decrease in production cost. India being a very vast country having diverse cropping systems with varying level of mechanisation and socio economic variability a common mechanisation strategy to increase productivity and profitability may not be applicable.

The transformation of mechanisation scenario is inevitable. Then challenge is to manage the gradual and evolutionary transformation with minimum social cost. The entire set of traditional activities needs not to be replaced by a new set of modern activities at once in order to enhance productivity and profitability. Certain farm operations need to be mechanised first then others until eventually the complete transition to mechanised farming is made. At present, “Selective Mechanisation” is highly relevant for diverse modern conditions. Setting up custom hiring services will be able to provide the machinery on need basis to small and medium farmers. Increase in farm power availability in production catchment will help in overall up-liftment of farmers in terms of productivity and profitability.

The impact of farm mechanisation has till now been able to steer the agriculture growth and further careful assessment of mechanisation needs an appraisal of available technology and formulation of policy framework to encourage appropriate mechanisation and support overall agricultural development objectives.

Present status of farm mechanisation: From the machine requirement point of view, the various farm operations are grouped as below:

a) Mobile operations or works which needs tractor or power tiller as prime mover e.g. ploughing, harrowing, levelling, seeding, planting & intercultural.

b) Stationery operations or works such as lifting of water for irrigation, portable power, sprayers, threshing , chaff cutting, crushing sugarcane, grinding & mixing livestock feed, rice hulling, transplanting rice seedlings.

With the increase in intensity of cropping, the turnaround time is drastically reduced. Hardly ten to fifteen days are left in between harvesting of previous crop and sowing of subsequent crop. So to do all these field operation in limited time, it is not possible without machine. Thus mechanization is inevitable. The different sources of power available on the farm for doing various mobile and stationary operations are discussed below:

Mobile Power Sources

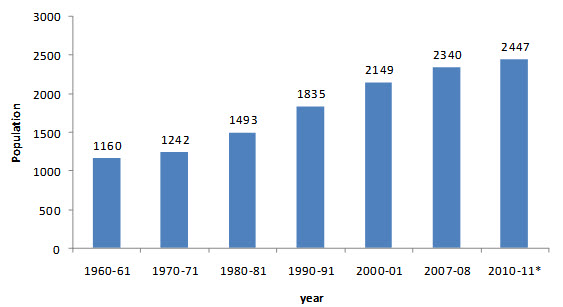

- Human Power (Men, women, and children): The average power availability from a male agricultural worker is considered 60 watts (0.06 kW) while from female worker it is considered as 48 watts (0.048 kW) and for child worker 30 watts (0.030 kW). The population trend of agricultural workers is given in Fig 1.1.

Fig. 1.1: Population trend of agricultural workers in India

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 *Projection

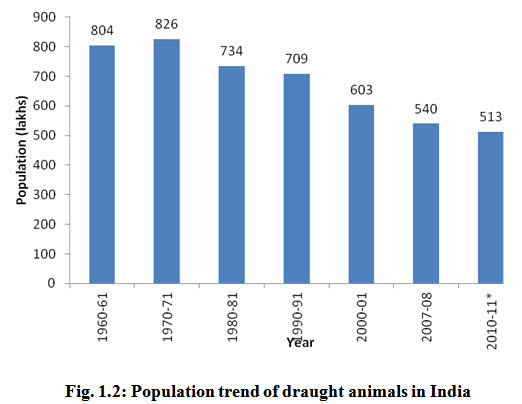

2. Drought animal Power: Bullocks, buffalos, camels and pack animals horses, ponies, mules and donkeys are used as a source of power for doing different agricultural and commercial activities. The population trend of draught animal is given in Fig. 1.2. activities. The population trend of draught animal is given in Fig. 1.2.

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 *Projection

Tractors: The cumulative population is given in Fig.1.3.

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 & Agricultural Research Data Book, 2011

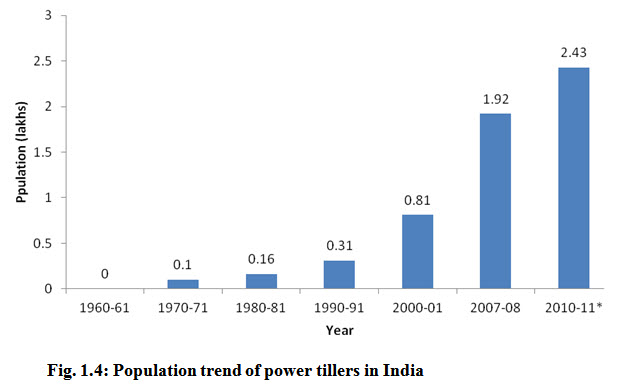

Power Tiller: Power tillers also called as walking type tractor are generally used in hill farming and land holding is small. The population trend of power tiller is given in Fig 1.4.

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

Self Propelled Machines: Rice transplanters, Power weeders, sprayers, reaper binder, combine harvesters have their own engine as source of power. These type of machine are called self propelled machine.

Stationary Power sources:

Diesel engine: Diesel engine is used in pump sets, sprayers, threshers, chaff cutters, sugar cane crushers and other stationary operations as source of power.

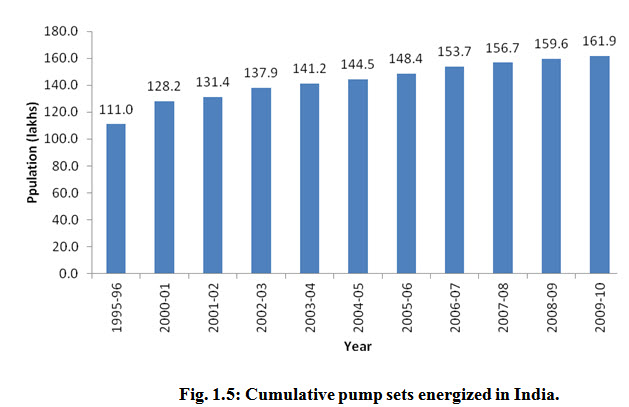

Electric Motor: These are used in pump sets, sprayers, threshers, chaff cutters, sugar cane crushers and other stationary operations as source of power. The cumulative pump sets energised in India is given in Fig.1.5.

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

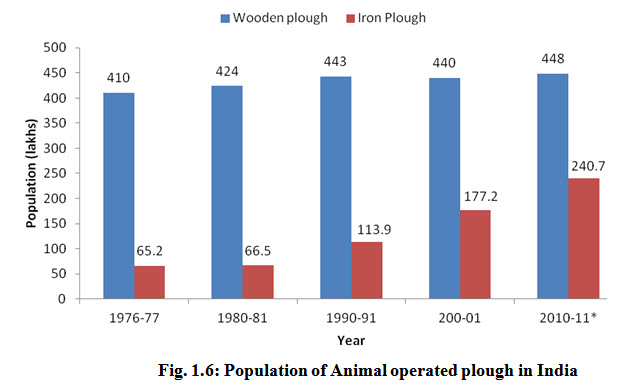

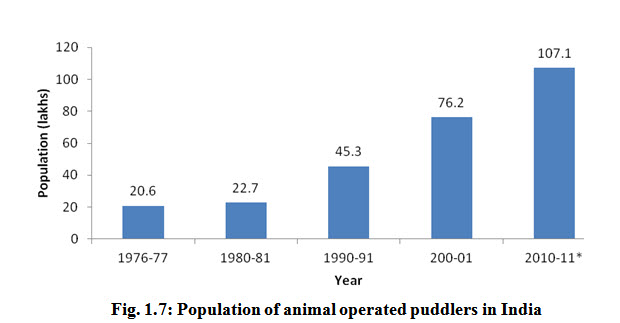

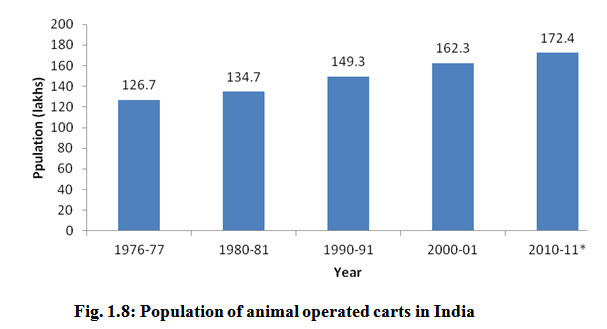

Animal operated implements: The population of animals operated plough puddlers and carts is given graphically in Fig. 1.6, 1.7, 1.8 respectively.

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

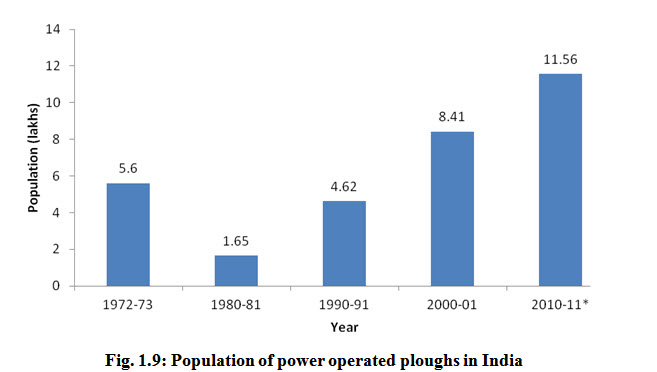

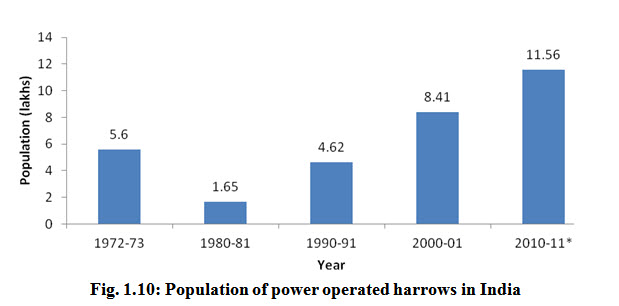

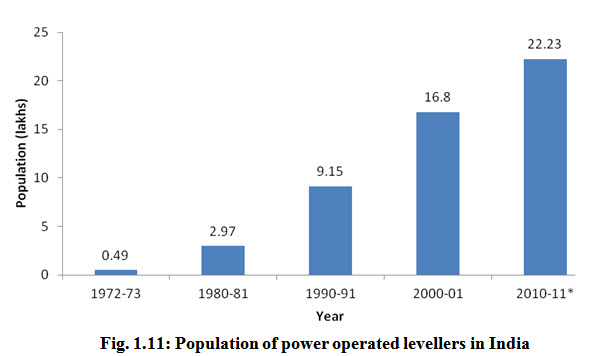

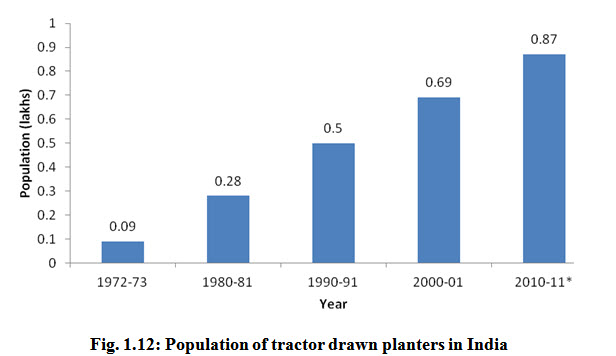

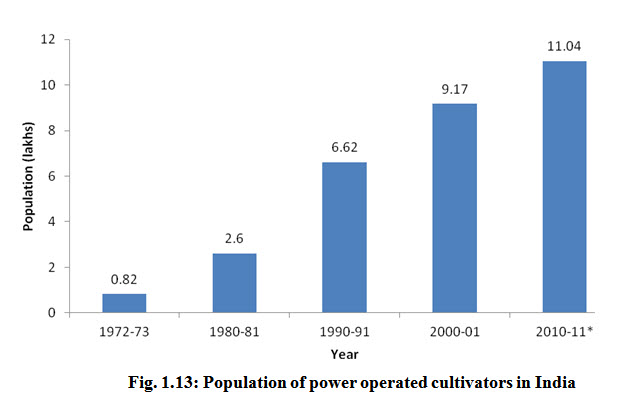

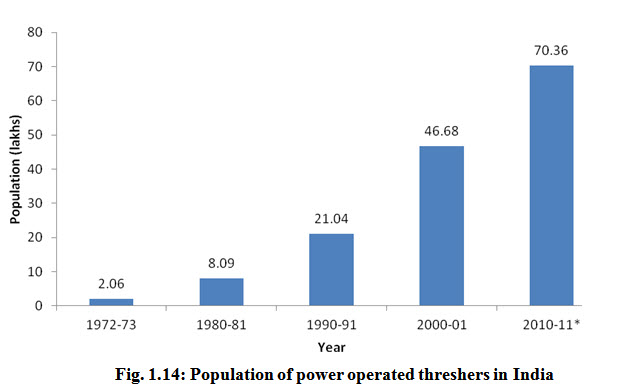

Tractor operated implement:- Population of tractor operated plough, disc harrow, cultivators, planter, levellers, thresher is given in. Fig. 1.9 to Fig. 1.14.

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

Source: Agricultural Engineering Today Vo. 34(4), 2010 * Projection

The total power availability in the country was 0.3 kW/ha in the year 1971-72 which increased is 0.76 kW/ha in 1991-92, 1.23 kW/ha in year 2001-02 and 1.78 kW/ha in 2011-12. The annual increase in availability of farm power is estimated as 0.03 kW/ha/year. The level of mechanization in the country has shown an increasing trend, however there has been contrasting disparity in its spread. The estimates indicates that the highest availability of power on farm (2005-06) was in the state of Punjab (4.03 kW/ha) followed by Haryana 2.90 kW/ha, Tamil Nadu 1.23 kW/ha, Andhra Pradesh 1.1 kW/ha and West Bengal 0.69 kW/ha respectively and only 0.35 kW/ha in Orissa. The mechanisation in western and southern states of the country viz. Gujrat, Maharashtra, Rajisthan and certain areas of Tamilnadu, Andhra Pardesh etc has increased with increase in area under irrigation. The pace of mechanisation in North-Eastern states has not been satisfactory due to constraints such as hilly topography, socio economic conditions, high cost of transport and lack of institutional financing and lack of farm machinery manufacturing industries. By and larger India is self- sufficient in mechanisation inputs and the Indian farmers have adopted mechanisation input for modernisation of their agriculture. Equipment for tillage, sowing, irrigation, plant protection and threshing have widely been accepted by them. The improved hand tools, animal drawn and tractor operated implement have been adopted more in these states where productivity per unit area has increased.