Site pages

Current course

Participants

General

Module 4. Concepts and application of management p...

Lesson-18 Agricultural Supply Chain Management

18.1 INTRODUCTION

The term agribusiness is a generic one that refers to various businesses involved in food production. Businesses do not exist in isolation - every business has suppliers of goods it needs, and buyers of the goods it makes/sells - each having the same driving forces and critical responses. The grouping of these businesses is called a chain of companies and tends to reflect the industry the businesses are involved in. The agri-industry sector is a large, multifaceted industry sector that exists worldwide, and involves a range of businesses that create industry specific (e.g. grains, sugar cane, timber, dairy, cattle/meat, fruit and vegetables, cotton, wool, to name a few) agri-industry chains that often exist across international boundaries.

18.2 SUPPLY CHAINS

We speak of a ‘supply chain’ when different actors are linked from ‘farm to fork’ to achieve a more effective and consumer-oriented flow of products. Such supply chains may include growers, pickers, packers, processors, storage and transport facilitators, marketers, exporters, importers, distributors, wholesalers, and retailers. Supply chain development can thus benefit a broad spectrum of society, rural and urban, in developing countries. A supply chain can be broken into three major parts (components): upstream, internal, and downstream.

The upstream supply chain: The upstream part of the supply chain includes the activities of a company (a milk producer, in our case), with its first-tier suppliers and their connection to their suppliers (referred to as second-tier and third-tier suppliers). The supplier relationship can be extended several tiers, all the way to the origin of the material (e.g., mining ores, growing crops). In the upstream supply chain, the major activity is procurement.

The internal supply chain: The internal part of the supply chain includes all of the in-house processes used in transforming the inputs received from the suppliers into the organization’s outputs. It extends from the time the inputs enter an organization to the time that the products go to distribution outside of the organization. The internal supply chain is mainly concerned with production management, manufacturing, and inventory control

The downstream supply chain: The downstream part of the supply chain includes all of the activities involved in delivering the products to the final customers. The downstream supply chain is directed at distribution, warehousing, transportation, and after-sale services.

Supply Chain Management: The function of supply chain management (SCM) is to plan, organize, and coordinate the activities along the supply chain. Today, the concept of SCM refers to a total systems approach to managing the entire supply chain.

18.3 THE SUPPLY CHAIN FLOWS

There are typically three types of flows in the supply chain: materials, information, and financial (money). In managing the supply chain, it is necessary to coordinate all of the flows among all of the parties involved in the chain.

Material flows: These are all physical products, raw materials, supplies, and so forth, that flow along the chain. The concept of material flows also includes reverse flows—returned products, recycled products, and disposal of materials or products. A supply chain thus involves a product life cycle approach, from “dirt to dust.”

Information flows: This includes all data related to demand, shipments, orders, returns, schedules, and changes in the data. It also includes customer feedback, ideas from suppliers to manufacturers, order flows, credit flows, information to customers, and so forth.

Financial flows: The financial flows are all transfers of money, payments, credit card information and authorization, payment schedules, e-payments, and credit related data.

18.4 SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT AND ITS BENEFITS

Managing supply chains requires an integral approach in which chain partners jointly plan and control the flow of goods, information, technology and capital from ‘farm to fork’, meaning from the suppliers of raw materials to the final consumers and vice versa.

In order to react effectively and quick to consumer’s demand, supply chain management is consumer-oriented. It aims at coordination of production processes. Supply chain management results in lower transaction costs and increased margins. Because of the many activities and aspects involved it demands a multidisciplinary approach and sustainable trade relations. Supply chain partnerships are based on interdependence, trust, open communication and mutual benefits. The advantages of the supply chain management approach are numerous. Some important advantages are:

Reduction of product losses in transportation and storage.

Increasing of sales.

Dissemination of technology, advanced techniques, capital and knowledge among the chain partners.

Better information about the flow of products, markets and technologies.

Transparency of the supply chain.

Tracking & tracing to the source.

Better control of product safety and quality.

Large investments and risks are shared among partners in the chain.

18.5 SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT TOOLS

A range of new supply chain management tools have been developed over the past decade. ‘Efficient consumer response’ (ECR) has been developed to increase the consumer orientation and cost-effectiveness of supply chains. New management systems have been implemented to improve logistics, increase the use of information and communications technologies and boost quality management (Lambert and Cooper, 2000). New generation cooperatives are emerging, strengthening the position of farmers’ groups and strategic partnering and vertical alliances are cementing sustainable partnerships throughout the supply chain.

Food safety concerns have led to the development of ‘integral chain-care’ tools such as social accountability, good agricultural practice (GAP), total quality management, and HACCP (hazard analysis at critical control points). Implementation of such tools throughout a cross-border supply chain enables chain partners to ensure the quality and safety of their products and guarantees acceptable social chain performance. Supermarkets in Brazil and Thailand, for example, have initiated total quality management programs and HACCP rules for perishables like fresh fish and meat.

Retailers (e.g., Walmart, Carrefour, Royal Ahold, Tesco and Sainsbury) have increasingly established their own quality standards (e.g., EUREP-GAP and BRC2) which suppliers must meet. Tracking and tracing systems are used to certify the quality of products and ensure transparency in the flow of goods throughout the supply chain. Implementing such standards and systems impacts not only the organization of supply chains, but also financial aspects of chain cooperation. These standards and systems are now being used in the agricultural sector and have proven their value in cross-border projects. Sharpened requirements for standards have prompted public and private actors to establish a variety of initiatives to build or strengthen agri-supply chains.

18.6 VALUE CHAIN

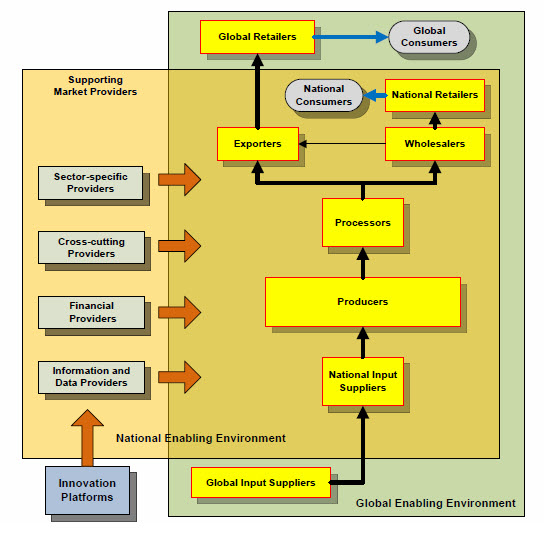

The value chain describes the full range of activities which are required to bring a product or service from conception, through the different phases of production (involving a combination of physical transformation and the input of various producer services), delivery to final consumers, and final disposal after use. The schematic diagram of value chain is presented in fig. 18.1.

A value chain links the steps a product takes from the farmer to the consumer. It includes research and development, input suppliers and finance. The farmer combines these resources with land, labour and capital to produce commodities. In the traditional selling system farmers produce commodities that are "pushed" into the marketplace. Farmers are isolated from the end-consumer and have little control over input costs or of the funds received for their goods. In a value chain marketing system, farmers are linked to consumers' needs, working closely with suppliers and processors to produce the specific goods consumers demand. Similarly, through flows of information and products, consumers are linked to the needs of farmers. Under this approach, and through continuous innovation, the returns to farmers can be increased and livelihoods enhanced. Rather than focusing profits on one or two links, players at all levels of the value chain can benefit. An integral component of the value chain is the agricultural supply chain, and in the literature these terms value chain and supply chain may at times be used interchangeably, or are at least closely related.

Fig. 18.1. An Overview of conceptual Value Chain

18.7 SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES BETWEEN A SUPPLY CHAIN AND A VALUE CHAIN

Supply Chain Management (SCM) emerged in the 1980s as a new, integrative philosophy to manage the total flow of goods from suppliers to the ultimate user and evolved to consider a broad integration of business processes along the chain of supply. Keith Oliver coined the term “supply chain management” in 1982. Oliver, a vice president in Booz Allen Hamilton’s London office, developed an integrated inventory management process to balance trade-offs between his clients' desired inventory and customer service goals. The original focus was the “management of a chain of supply as though it were a single entity, not a group of disparate functions,” with the primary objective of fixing the suboptimal deployment of inventory and capacity caused by conflicts between functional groups within the company.

SCM evolved quickly in the 1990s with the advent of rapid response initiatives in textile and grocery industries, and was refined by large retailer Wal-Mart who used point-of-sale data to enable continuous replenishment. Supply chain is a term “now commonly used internationally to encompass every effort involved in producing and delivering a final product or service, from the supplier’s supplier to the customer’s customer”. As the name implies, the primary focus in supply chains is on the costs and efficiencies of supply, and the flow of materials from their various sources to their final destinations. Efficient supply chains reduce costs.

In common parlance, a supply chain and a value chain are complementary views of an extended enterprise with integrated business processes enabling the flows of products and services in one direction, and of value as represented by demand and cash flow in the other. Both chains overlay the same network of companies. Both are made up of companies that interact to provide goods and services. When we talk about supply chains, however, we usually talk about a downstream flow of goods and supplies from the source to the customer. Value flows the other way. The customer is the source of value, and value flows from the customer, in the form of demand, to the supplier. That flow of demand, sometimes referred to as a “demand chain” is manifested in the flows of orders and cash that parallel the flow of value, and flow in the opposite direction to the flow of supply. Thus, the primary difference between a supply chain and a value chain is a fundamental shift in focus from the supply base to the customer. Supply chains focus upstream on integrating supplier and producer processes, improving efficiency and reducing waste, while value chains focus downstream, on creating value in the eyes of the customer. This distinction is often lost in the language used in the business and research literature.

18.8 IMPORTANCE OF VALUE CHAIN

There are three main sets of reasons why value chain analysis is important in this era of rapid globalization. They are:

With the growing division of labour and the global dispersion of the production of components, systemic competitiveness has become increasingly important

Efficiency in production is only a necessary condition for successfully penetrating global markets

Entry into global markets which allows for sustained income growth – that is, making the best of globalization - requires an understanding of dynamic factors within the whole value chain

18.9 TRADITIONAL SELLING SYSTEMS V/S VALUE CHAIN MARKETING SYSTEM

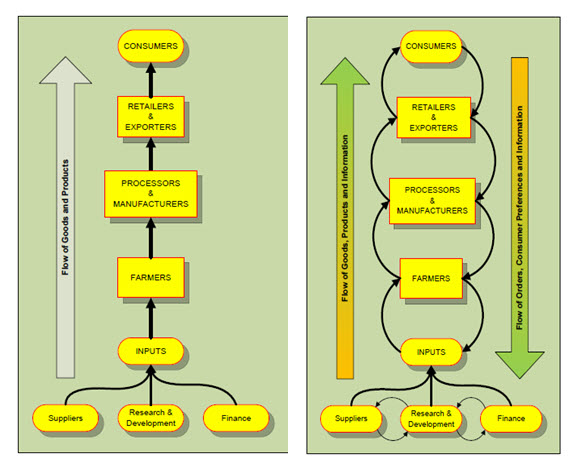

In the traditional selling system, farmers produce commodities that are "pushed" into the marketplace. Farmers are generally isolated from a majority of end-consumer and have little control over input costs or process received for their goods. The primary exception is where local farmers sell produce in local markets and where there is a direct link from farmer to consumer. In most traditional selling systems formers/producers tend to receive minimal profit. Any integration up or down the value chain can help.

Market “Push” tends to be based on independent transactions at each step, or between each node. Products may often be sold into a crowded and competitive market. The farmers is largely isolated from the consumer, and from the demands and preferences of consumers. Research and Development is focused on production and on reducing costs of production, and may not take account of other steps, links, or dependencies in the chain (e.g. environmental or social costs).

In a Value Chain marketing system, farmers are linked to the needs of consumers, working closely with suppliers and processors to produce the specific goods required by consumers. Using this approach, and through continuous innovation and feedback between different stages along the value chain, the farmer's market power and profitability can be enhanced. Rather than focusing profits on one or two links, players at all levels of the value chain can benefit. Well functioning value chains are said to be more efficient in bringing products to consumers and therefore all actors, including small-scale producers and poor consumers, should benefit from value chain development.

The market “Pull” is based on integrated transactions and information. Consumers purchase products that are produced according to their preferences. The farmer becomes the core link in producing the products that the consumers desire. Research and development, whilst including techniques targeted at increased production, is also focused on consumer needs, and attempts to take account of all of the links, and dependencies in the value chain, e.g. processing, environmental and social costs or considerations, as well factors such as health impacts, education and learning. Communication is in both directions. It is important that both consumers and processors are made aware of factors limiting production, just as much as farmers and other producers are made aware of consumer requirements (Fig. 18.2.1 & 18.2)

Fig18.2.1: Traditional Marketing System Fig.18.2.2: Value Chain Marketing System

INDIA’S AGRI SUPPLY CHAIN

Issues and Challenges:

-

Lack of Supply Chain Integration

-

Sidelining Arhathias (middleman) from the value chain

-

Difficulty in credit recovery and reluctance of farmer in approaching banks

-

Low penetration of ‘one-stop-shops’(due to huge capital requirements)

-

Inefficient buy back system (purchase of farm output)

-

Inefficient compensation delivery system in case of product failure

Opportunities:

-

Government’s impetus to private extension services

-

One-stop-shop can act as facilitators of microfinance

-

New channel evolved can be used by FMCG and consumer durables

Suggested Reading:

-

Sunil Chopra & Peter Meindl. Supply Chain Management –PHI

-

R.P. Mohanty & S.G. Deshmukh. Essentials of Supply Chain Management. Jaico Publishing House

-

Altekar. Supply Chain Management: Concept & Cases. PHI