Site pages

Current course

Participants

General

MODULE 1. Electro motive force, reluctance, laws o...

MODULE 2. Hysteresis and eddy current losses

MODULE 3. Transformer: principle of working, const...

MODULE 4. EMF equation, phase diagram on load, lea...

MODULE 5. Power and energy efficiency, open circui...

MODULE 6. Operation and performance of DC machine ...

MODULE 7. EMF and torque equations, armature react...

MODULE 8. DC motor characteristics, starting of sh...

MODULE 9. Polyphase systems, generation - three ph...

MODULE 10. Polyphase induction motor: construction...

LESSON 18. DC shunt motor characteristics

The Shunt Motor

The shunt motor is connected in the same manner as a shunt generator, that is, its field is connected directly across the line in parallel with the armature. A field rheostat is usually connected in series with the field. If mechanical (braking) load is applied to any motor, it immediately tends to slow down. In the case of the shunt motor this decrease of speed lowers the back electromotive force, as the flux remains substantially constant. If the back emf is decreased, more current flows into the armature according to E = V - IaRa. This continues until the increased armature current produces sufficient torque to meet the demands of the increased load. The suitability of a motor for any particular duty is determined almost entirely by two factors, the variation of its torque with load and the variation of its speed with load.

In the shunt motor the flux is substantially constant. Therefore, from torque equation, the torque will vary almost directly with the armature current. For example, in figure below, when the armature current is 30 amp, the motor develops 40 lbft torque, and when the current is 60 amp, the motor develops 80 lbft torque. That is, when the current doubles the torque doubles.

Fig. 8.7 Shunt and series motors; torque-current curves.

The speed of a motor varies according to equation ![]() In the case of the shunt motor, K, V, Ra, and φ are all substantially constant. Therefore, the only variable is Ia. As the load on the motor increases, Ia increases and the numerator of this equation decreases. As a rule the denominator changes only a small amount. The speed of the motor will then drop with increase of load, as shown in the next figure. As IaRa is ordinarily from 2 to 6 per cent, of V, the percentage drop in speed of the motor is also of same magnitude. For this reason the shunt motor is considered a constant speed motor, even though its speed does drop slightly with increase of load. Owing to armature reaction, φ ordinarily decreases slightly with increase of load and this tends to maintain the speed constant. Occasionally the armature reaction is sufficiently great to give a rising speed characteristic with increase of load.

In the case of the shunt motor, K, V, Ra, and φ are all substantially constant. Therefore, the only variable is Ia. As the load on the motor increases, Ia increases and the numerator of this equation decreases. As a rule the denominator changes only a small amount. The speed of the motor will then drop with increase of load, as shown in the next figure. As IaRa is ordinarily from 2 to 6 per cent, of V, the percentage drop in speed of the motor is also of same magnitude. For this reason the shunt motor is considered a constant speed motor, even though its speed does drop slightly with increase of load. Owing to armature reaction, φ ordinarily decreases slightly with increase of load and this tends to maintain the speed constant. Occasionally the armature reaction is sufficiently great to give a rising speed characteristic with increase of load.

Fig. 8.8 Typical shunt motor characteristics

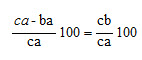

Speed Regulation: The speed regulation of a shunt motor is almost identical with the voltage regulation of a shunt generator. It is the difference in the no-load and the rated-load speed divided by the no-load speed. In the figure, the percentage speed regulation is hence

The figure 8.8 shows the three essential characteristics of a shunt motor, the torque, the speed, and the efficiency, each plotted against current. It will be noted that the shunt motor has a definite no-load speed. Therefore it does not run away when the load is removed, provided the field circuit remains intact. Shunt motors are used where a constant speed is required, as in machine shop drives, spinning frames, blowers, etc. There is an erroneous impression that shunt motors have a low starting torque and therefore, should not be started under load. Starters are usually designed to allow 125 per cent of full load current to flow through the armature on the first notch. Therefore, the motor develops 125 per cent, of full-load torque at starting. By decreasing the starting resistance, the motor could be made to develop 150 per cent, of full-load torque without trouble.